Is an author's preface really necessary?

Shawn Thompson

6/1/202410 min read

Not everyone wants to read an author’s preface, but here it is anyway. You decide for yourself. Yes, I’m the author of this book, as much as anyone can claim to be the author of anything. We have many influences in our lives. We are aware of some of the influences and unaware of other influences. For me, I’ve been influenced by numerous people and numerous books, in addition to my personal experiences, such as trekking through the jungles of Southeast Asia, visiting inside more prisons than most people and riding a navy submarine through a gale. That means getting very hot and sweaty, feeling locked in and getting terribly seasick. It also means that I made observations in unusual situations and asked a lot of questions along the way.

What’s the point? The point is that simply asking questions is a way of entering experience and finding fulfillment. Asking anybody, anywhere, anything, under any conditions. Being curious, genuinely curious. In the spirit of Socrates, Zen Buddhism, psychoanalysis, scientific inquiry and people who ask annoying questions, this book will ask annoying questions. This book will claim that the question has more power and more importance than the answer, contrary to the western rational tradition where the answer is what is most important. It is a dangerous and radical idea that the question has more power than the answer. It begins with the annoying questions of Socrates in ancient Athens and with the practice of Zen Buddhism. Socrates didn’t bend to the structure of power in the priests, politicians, experts and leaders in his society. Socrates asked questions and, in the mere act of asking questions, he was challenging power, expertise and control. It was a shift in power that reduced the justification for the power that was exerted over people in society. The power of the questioner increased and the power of the person in authority with the answers decreased. It was a shift towards greater democracy. In Zen Buddhism, a similar change was happening in spirituality.

This book will also claim that better questions depend on unshackling curiosity from the way that curiosity is discouraged and controlled in society. This book will claim that there can be peace of mind in doubt. Does that sound bizarre? I agree, but nevertheless, let’s pursue these bizarre notions for the moment. What is curiosity and can it be developed? What if the question has more power and more importance than the answer? Where could that go? What if there is peace of mind in doubt? Is that possible? Who is good at creating original questions? What if Socrates had died before Plato knew him? What did Socrates dream? What if we think like Franz Kafka? What does the Zen koan mean that the dead tree sings in the wind? Questions, questions, questions.

I enjoyed the freedom to ask questions when I worked for almost 18 years as a newspaper journalist, in ancient pre-digital times when some speculate that there were fewer distractions. I didn’t need to be an expert in anything. I could learn as I went along. Perfect. Nobody expected more of a journalist. Many people thought of them as rabble. But I kept asking questions. I was like Socrates without thinking about it. I was expected to ask good questions and there was no reliable manual on that. The lore in journalism is the story that one time a rookie reporter came to the editor with a story typed out. The editor snuffed his cigar out on the paper, saying, do it again. No directions. Just do it again. So, as a journalist you wanted to avoid being told that even though you weren’t told how. That’s the lore, the ancient folklore of journalism. Then, later, when I came to teach in a university for 25 years - which is far too long - I felt the pressure to promote dogma, which is what the students, having been indoctrinated for too many years, wanted and expected. Students didn’t ask good questions and didn’t think that their role was to ask good questions. As part of that, I probably produced too much dogma and too few good questions. But I still wanted to teach students how to ask questions, better questions, which is how this book began. I felt that I would be a better teacher if I could teach students how to ask better questions. Not everyone understood that, including other faculty. The knowledge was already established. Why did anybody need to learn to ask better questions?

So, do you feel cheated so far that I’m not a certified Zen master, not a certified philosopher, not a certified scientist? If so, fine. Look for a book that suits you better. This is not what you seek. I did manage to publish a book about orangutans – or how human beings relate to the mystery of the consciousness of orangutans – without being a certified anthropologist. But that gave me a freedom from a scientific focus to pursue wider questions about orangutans. That was liberating, even if the book was not a popular success. Popularity depends on what people are seeking, not always on what they need, and some people don’t want to be told what they need. And yet, being author of an unpopular book on an obscure topic did earn me a role as an “expert” in orangutans to testify in a high-profile court case in Buenos Aires to decide whether an intelligent creature like the orangutan Sandra - who had been born in a zoo in Germany and had lived her entire life in zoos, was traded and sold in captivity, her lone child taken from her and sold to another zoo - should be released from the zoo in Buenos Aires. I was interviewed more prominently about the trial of that one orangutan in Buenos Aires than about my wonderful book on orangutans. But the issue was good and I am glad that it got attention, if only as a curiosity.

Doing the book, I did get to spend time with orangutans, which I appreciate. I was curious about them and they were curious about me. We shared the trait of curiosity. It was one way to communicate without language and form a relationship. Unlike students, who don’t have much curiosity left in them, orangutans pay attention. Was that experience with orangutans a Zen moment? I don’t know and why would I need to know that in order to have the experience? That experience with orangutans made me ask, Why are orangutans curious? Why is curiosity a shared trait? If I could be given an infinite memory to remember everything but would have to give up curiosity in exchange – which is how bargaining for miracles seems to work in the lore – I don’t think I should do it. I don’t see much good to knowledge without curiosity. I imagine that in curiosity there may be peace of mind, that curiosity can embrace doubt. I am seventy years old as I write this book. I hope that when I get much older and my memory is fading little by little like the sky clearing of clouds, I will still be as curious as an orangutan. I wonder what it would be like to have no memory, only constant curiosity. Maybe I’ll experience that some day. If I do, I wouldn’t know that it is a Zen experience, but why would that knowledge matter anyway?

Before I forget, I should finish the story of the orangutan trial, if you are curious and want to know. I knew enough about intelligence in orangutans and what the judge would need to know in a legal context to render a verdict. I also had two friends who were actual experts in orangutans, Leif Cocks and Gary Shapiro, and so I asked them to join me to form a panel of three. I would draft a report to the judge with the certified excellence of their understanding of orangutans, plus what I’d learned from talking to primatologists and zookeepers, plus my ability to translate science for the judge in a way that made legal sense. In the end, the judge ordered Sandra released from the zoo, much to the annoyance of the authorities in Buenos Aires. How did an orangutan manage to win a court case? Baffling. Sandra was sent to retirement in a sanctuary in Florida that my little panel and I had recommended. Lots of human primates like to retire in Florida too. Sandra needed to be retired to a sanctuary because a zoo-bred orangutan wouldn’t know how to survive in the jungle. That’s what captivity does to you. Be warned. If you submit to captivity, you will be like a zoo-bred orangutan. The cage will seem like home to you.

Incarceration and captivity were themes of mine as a writer, which I explored in a book about prisoners in federal prisons in Canada and the United States. I started the book when I was a prison reporter with extraordinary access to prisons and prisoners. In writing the book, I decided that I should spend at least a little time in a prison cell – without becoming a certified offender. I’d had contact as a journalist with the warden of Canda’s oldest federal prison, Kingston Penitentiary, in Kingston, Ontario – prisons don’t have imaginative names like churches, like the Church of the Good Thief in Kingston, close to the prison. This prison was visited by Charles Dickens himself in 1842. Imagine that. Dickens was a prison tourist. One of my scoops as a journalist was interviewing a former guard who revealed to me that he had discovered an unknown letter from Dickens. Dickens wrote the letter privately to a guard at the prison and it was hiding in a dusty stack of old papers that interested nobody. Anyway, the warden of the prison trusted me enough to incarcerate me in a cell in Kingston Penitentiary for Easter weekend, perhaps thinking that I would somehow be faithful to the experience. I didn’t romanticize being in prison. I didn’t have a romantic experience there for my brief stay. By the way, the idea of the solitary cell arose in western culture from the example of monks in solitary cells. The idea was that solitude and contemplation would lead to revelation and redemption. But inside a prison, there is a deeper prison punishment called solitary confinement. I didn’t feed redeemed from being in a prison cell, but maybe I am easily distracted. And yet I did explore the minds of prisoners in captivity, writing letters back and forth. It doesn’t seem that captivity produces a better human being.

Anyway, to continue the story, I hauled my half-finished prison book west with me when I was hired to teach in a small university in the mountains of British Columbia on the far side of Canada. Just about every place in Canada has a far side. Come to Canada if you want to experience a far side. One advantage of being hired to teach in a university is that you aren’t certified as a teacher, like the better-educated teachers in public school and high school. In a university, you are an uncertified teacher, because, apparently, knowledge by itself is enough. If you have enough knowledge, maybe you can teach. Great. You can learn how to teach as you go along. The students will appreciate your knowledge, despite what the dean thinks of you. Nobody will ask you difficult questions. At the university, the other uncertified teachers told me not to finish my book on prisoners because it wasn’t academic enough. Yes, I agree. It was not an an academic book. It was me conversing by letter with prisoners at night in their cells when they could be truthful to their experience. I finished the book.

Years later, it happened again. The same thing. I was told in the university that I couldn’t work on the topic of this current book because I’m not certified in any of the fields explored in this book. And I certainly don’t want to pretend that I am. I am not a master in Zen Buddhism, not a Zen Buddhist monk, although their literature fascinates me. I am not a psychotherapist, although I’ve met people who could use therapy. I don’t have a degree in philosophy. But why can’t anyone learn about asking questions from philosophy, Zen Buddhism, psychiatry and science? Why this exclusion? Why should I be forbidden from inquiring how journalists and others would benefit from learning how those in the fields of philosophy, Zen Buddhism, psychiatry and science, learn to ask better questions? Do you have to be certified to practice Zen Buddhism? Can philosophy not tolerate someone without a degree in philosophy?

I understood how the faculty thinks. It made sense from their point of view. They were like a tribe that had lived and grown together. They had gone to graduate school for many years and then stayed in the education system to teach. They had been taught that information becomes “scholarly” and that this “scholarly” information is the exclusive purview of scholars. The faculty wanted to perpetuate that thinking and the power that comes with it. Even using the wider terms of “interdisciplinary,” “multidisciplinary” and “transdisciplinary” discussion at other universities, the discussion is still limited to scholars and controlled by them. There is the same temptation in spirituality and politics, that knowledge is the purview of the certified spiritual and political officials and can’t be questioned. So, without thinking about it, the faculty at my university automatically opposed this book. Plus, I had to pay for parking on campus just to work there. But why can’t everyone be like Socrates and learn to ask better questions? Isn’t that healthy for society? What if students could learn to ask better questions? Why not teach that? Why not challenge ourselves by questioning ourselves?

I understand that I am not an expert in many things, but I believe that the scope of the topic of this book needs more freedom, more democracy. Readers can decide what helps them. The best that I could do was try to finish this book by listening to others and then think about it like Socrates would. Imagine Socrates wandering in the agora, outside the official, organized and approved institutions and forums for discussion in old Athens. That was his choice. Socrates chose to converse outside the standard forums of discussion in the way that he wanted, individual to individual. He was very skillful at asking questions and resisted the pressure to produce a conclusion when he didn’t think that there was one. Maybe life is inconclusive too. Maybe that’s the nature of the universe and infinity - the unfinished story, the endless question, the process of inquiry itself. Who can know?

I imagine that this this book is best if it is honestly intended for members of the uncertified rabble like me. We live without expertise, but, then, what kind of expertise do we need to live? I apologize for sounding academic or professorial or dogmatic at times. I can’t avoid it. It’s a curse of mine. Please excuse those moments of forgetfulness. It was a real challenge for me to find a way to write a book about the primacy of the question without doing the opposite. I didn’t always succeed. Maybe my solutions to that don’t appeal to you. You will have to decide. Don’t keep reading just to antagonize yourself. Let go of that. Ask yourself,Has this book helped me to ask better questions? Has this book helped me to understand what questions are? What questions am I asking now? I can’t decide that for you.For me, if you are interested, I enjoyed writing this book. I don’t want to stop. Writing this book reminds me of one glorious hot summer when I was thirteen and picked up a copy of the Socratic dialogues The Last Days of Socrates, with the Euthyphro, the Apology, the Crito, and Phaedo. In a sense, maybe that summer didn’t end. Maybe I should keep reading. I am in my seventies now and I doubt that I will ever write another book. But, who knows? Hopefully, I will remain curious. Hopefully, so will you. At least you got this far. Thanks.

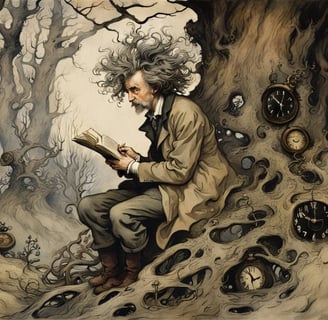

Image from an original idea by Shawn Thompson

Can you begin with a question and end with a question?

Making contact:

© 2024. All rights reserved. Copyright Shawn Thompson

Socratic Zen on Meta (Facebook) as an interactive public forum

Socratic Zen on Youtube (under construction)

The font used for titles for this website is Luminari, an exquisite yet restrained script font designed by a company called CanadaType. "Its majuscules are particularly influenced by the versals found in the famous Monmouth psalters, as well as those done by the Ramsey Abbey abbots in the twelfth century."

Find an explanation at https://canadatype.com/product/luminari/