Chapter 5: What is the price of speaking dangerous truths and is it worth it?

Wherein we contemplate how the spirit of Socrates might return at a time of the recurring danger of sophists in democracies.

Shawn Thompson

5/27/202420 min read

For the journalist Marie Colvin, in the end the truth caught up with her. The 56-year-old journalist died exposing the brutal truth of the Syrian government’s destruction of its own citizens in trying to eradicate the opposition of the Sunni Muslim opposition.

Colvin, an American, knew she was risking her life in Syria in 2012 as a journalist with over 25 years with the British newspaper The Sunday Times. Colvin courageously sought out stories in danger zones where civilians were savagely victimized, even after it was said that she was “crippled by bouts of post-traumatic stress disorder” and asked the questions that others didn’t want asked. Her questions were dangerous. Colvin covered death and destruction in Chechnya, Kosovo, Sierra Leone, Zimbabwe, Sri Lanka, East Timor, Libya and Syria. She experienced the unending condition of suffering and conflict in human. affairs. She exposed the suffering, but it did not end. In 2001, Colvin lost an eye in the explosion of a rocket-propelled grenade fired by the Sri Lankan army and thus acquired her signature eye patch.

The example of the life and death of Marie Colvin illustrates an essential problem in human affairs: an understanding of what is happening in the society is confused by sophistry, “alternate facts,” and “post-truth” quarrels. The truths that society needs to hear require the courage to take serious risks for an important purpose. This fits what the French philosopher Michel Foucault analyzed as the particular form of parrhesia, of speaking the truth, in Socrates, Plato and ancient Greek and Roman culture. Foucault makes the distinction that the particular parrhesia of Socrates speaking the truth requires courage.

Socrates himself, a solder who fought on the battlefield during the Peloponnesian War, was preoccupied with defining courage, a virtue important for the Greeks. Socrates debates courage in the Laches. Part of the discussion in the Laches is whether true bravery requires knowledge and the ability to be discriminating or can someone without knowledge of what bravery is be brave. Can someone be accidentally brave or recklessly brave or unintentionally brave? Is bravery a behaviour, a character trait or a kind of knowledge in action? Plato respected the courage of Socrates and created a model of courage off the battlefield through Socrates. That wasn’t debatable in the mind of Plato. In a similarly discriminating way, Foucault analyzed the nature of parrhesia, an ancient Greek term that Foucault applies to Socrates as a courageous truth-seeker, analyzed by Foucault dealing in part through the Laches.[iii] Some truths are essentially dangerous because they threaten structures of power and influence and thus require the virtue of courage; the risk to the person who speaks this truth is a measure of the importance of the truth.

What if this form of truth is forged in the act of acquiring it by the agent who suffers and experiences the agon? If risk is an essential part of this form of truth, can this truth then exist without a human agent, someone like a Marie Colvin or a Martin Luther King, Jr. or a Socrates? What if Socratic inquiry is a wisdom and truth that is inseparable from virtues, such as courage, moderation, humility, justice and piety, themselves often the subject of the early dialogues as well as what the dialogues are attempting to create in the individual and, by proxy, in the reader?

In terms of the historical Socrates, as James Zappen explains in his book The Rebirth of Dialogue – a book about Socrates and the Russian philosopher of dialogue, Mikhail Bakhtin – the debates of Socrates about the role of rhetoric in Athens were a courageous criticism of the leader Pericles and of the unethical pursuit of empire at a time of the decline of the power of Athens. It must have been offensive for the fellow citizens of Socrates to listen to Socrates exposing a shared folly and stupidity in them that leads a great civilization to the fall of its empire. The question is, as raised by Foucault, Do different truths have different values and if so, what gives value to the truth? Are the truths that are dangerous a different kind of truth, a more important truth, a truth that gains its importance because it is dangerous? Is a truth of greater value because it is dangerous and because it requires courage? This is where Foucault takes Socrates in the lectures of Foucault collected in The Courage of Truth and Discourse and Truth and Parresia. From the example of Socrates, as Plato would be aware, it takes courage to pursue these dangerous truths. In following a dangerous wisdom, the courageous and virtuous Socrates, as Plato recalls him and memorializes him, risks his life to be faithful to the truth as he sees it and is sentenced to death. Thus Socrates, a former soldier with a history of courage on the battlefield, lives the truth of the courageous process of inquiry that he proposes despite the real risk of physical harm to himself.

Socrates is a figure in the Laches that can be trusted to speak bravely and to understand the truth of what he says because he has proved his bravery in dangerous situations. Socrates is as courageous in asking questions as he was courageous on the battlefield in the campaign where Laches was the general and had witnessed himself the bravery of Socrates.[v] Socrates defence of himself on trial in the Apology, the first dialogue written, neither seeks mercy nor tries to win the assembly with evasions and sophistry. It might seem a poor defence if Socrates is not clever in manipulating the perceptions of the assembled jury to save himself. But that is how Socrates distinguishes himself. That is how he is true to his ethics. His defence of himself is defiant in a way that is dangerous to him at the moment his life is at risk. The defiance is a demonstration of courage. There is no retreating on this battlefield. When Socrates speaks in his defence at his trial, he embodies the courage he has shown consistently in his life. Socrates not only speaks the truth at his trial but is making his life a truth.

COURAGE, RISK AND INCONVENIENT TRUTHS

In the analysis of parrhesia by Foucault, the truth is bound to the virtue of courage in taking a serious and justified risk to tell a truth that is important and what is said is expressed in a true and unembellished way. Foucault was examining the risk in the act of telling the truth, but the terms for risk could be expanded in journalism and public affairs to also include other risks to the journalist, such as being present at scenes of violence, natural disaster and epidemics. Like Socrates on trial, Marie Colvin is defiant to find the truth at the risk of her life. She enters the war zone of Syria illegally and covertly because the government has forbidden admission to western journalists. Colvin is exposed to two types of risk at the same time: there is the risk of being a target by those who don’t want her to tell the truth; and the risk of being in a war zone where everybody is a target. Eliminating witnesses is one way to control what is known and a form of censorship. In Colvin’s case, the threat in Syria is as real to the journalist as to the citizens. The difference in the threat is that the journalist lives the risk as a conscious and willed choice, which is a significant difference and a different form of courage and truth-telling that, following the logic of Foucault, would distinguish the role of the journalist and political protesters from other roles.

Of course, the death of a journalist is an extreme version of risk, of which the Committee to Protect Journalists and Human Rights Watch keeps a record of the number of journalists killed around the world a year, from a high of 70 confirmed in 2007, to 48 confirmed for 2016. But the risk could be also be injury, imprisonment, exile, firing, legal action, ridicule, denigration, mistrust, loss of access to sources, social ostracism, or illnesses such as post-traumatic stress disorder.

Photojournalist Paul Conroy, in his book Under The Wire about the exploits of Marie Colvin and himself together behind the scenes in Libya and Syria, connects risk and courage with the mission to reveal the truth at any cost. The book is based on premises about courage and the mission of journalism that are unstated, apparently because they are believed to be a clear ideal norm that needs no explanation or defence.

From the perspective of parrhesia, the ultimate truths of journalism need the action of the journalist to be a witness, to be a vital body and soul that endure suffering and to be courageous and willingly exposed to real and justified risk. The journalist understands this essential hidden value in this truth of journalism.

And yet the standard narrative of the “news” promotes an abstract truth by removing the presence of the writer from the story. Personal pronouns disappear. The questions and exchange of an interview disappear. The acts of the journalist as a witness disappear. When that happens to the narrative, the journalist is distanced from the audience. A connection is broken between the audience and the journalist, which may create a distrust of the message and of the journalist that the style of narrative was actually meant to avoid.

As with Foucault’s explanation of parrhesia and truth-telling, journalists like Marie Colvin and Paul Conroy live their lives intentionally to embody truths bound with necessary and justified risks. These risks are not irrelevant to the truth, but part of what makes the truth what it is, and would define journalism as a specific form of truth-telling.

FOUCAULT AND PARRHESIA

What did Foucault mean in his analysis of the ancient concept of parrhesia and how can that be adapted and brought up to date with journalists like Marie Colvin or political protesters?

In his two years of Foucault’s public lectures from 1982-1984 at the College of France published in two volumes as The Courage of Truth and The Government of Self (and never developed into a book by Foucault before his death in 1984), Foucault defines parrhesia as the courageous act of telling a truth bluntly, freely and frankly that creates risk for the speaker. Foucault says that parrhesia is “a way of telling the truth that lays one open to a risk by the very fact that one tells the truth.” Originally rooted in political practice 404, “what defines the parrhesiastic statement, what precisely makes the statement of its truth in the form of parr[h]esia something absolutely unique among other forms of utterance and other formulations of the truth,” says Foucault, “is that parr[h]esia opens up a risk.” A scientist or a teacher may tell the truth, but that is a different kind of truth that may not require risk. “Everyone knows, and I know first of all,” says Foucault in a lecture, “that you do not need courage to teach.” Maybe.

Parrhesia has the “agonistic structure” of adversaries, says Foucault. It is “a truth which is so violent, so abrupt, and said in such a peremptory and definitive way that the person facing [the parrhesiast] can only fall silent, or choke with fury, or change to a different register ….[T]he person addressed is faced with a truth which he cannot accept, which he can only reject, and which leads him to injustice, excess, madness, blindness…” The parrhesiast may “provoke the other’s anger, antagonize an enemy, he may arouse the hostility of a city, or, if he is speaking the truth to a bad and tyrannical sovereign, he may provoke vengeance and punishment. And he may go so far as to risk his life, since he may pay with his life for the truth he has told,” says Foucault. “So it is the truth subject to the risk of violence.”

Foucault was analyzing truth-telling in ancient Greece through Plato, the playwright Euripides, the historian Plutarch, Demosthenes, Seneca and others, with an emphasis on Socrates, Plato and Euripides. One of the main examples Foucault gives of the truth as a risk are the conviction and sentencing to death of Socrates, which Plato explores in the Apology and other dialogues, In Foucault’s analysis, ancient philosophical parrhesia is distinguished from political parrhesia as pure ethical parrhesia or truth-telling for the benefit of the individual soul, even though an audience is also needed. In comparison, political parrhesia is for the benefit of the political unit, society and the city or polis.

JOURNALISTIC PARRHESIA

In his 319-page book Under the Wire, what the photojournalist Paul Conroy says about himself and Marie Colvin becomes clearer by applying the concept of parrhesia. Are Conroy and Colvin courageous truth-tellers and what conditions would they have to meet to be courageous truthtellers?

The situation in Syria was dangerous for Colvin and Conroy and they knew it. The opposition of the government of Syria to the truth of what was happening in Syria is clear. The Committee to Protect Journalists says in an article about the death of Marie Colvin, “By controlling local news reports and expelling or denying entry to dozens of international journalists, the Syrian government had sought to impose a blackout on independent news coverage after the country's uprising began in early 2011.” Syria was listed at one time by the Committee to Protect Journalists in 2017 as the third deadliest country for journalists in the world, after Iraq and Mexico. From 2016 to 2011, Syria was consistently number one.

Conroy explores in his book what journalists do to collect the information for the story, all that is not normally included in the narrative because it is commonly assumed to be extraneous to the truth and to the narrative. But Under The Wire is an account of bearing witness to the truth of journalism as inscribed in the body and soul of the journalist by being there and by experiencing the truth and the opposition to the truth. Colvin’s eye patch is a natural symbol of that. Symbolically, Colvin is wounded by what she sees but has better sight than others because of how far she sees into the truth. She has earned her sight by losing it. If the eye patch were used in a work of fiction as a symbol, it would seem to be the artificial device of a naïve author. Instead of the single eye of Marie Colvin, Conroy uses the single eye of a camera lens to bear witness to inconvenient truths. Under The Wire largely consists of getting in and out of crisis zones, calculating and timing the risk to be closest to the dangerous event at the last possible moment, managing anxiety and emotion, managing others, sometimes by concealing the truth to family, friends and colleagues. Bearing witness to truth has that kind of sacrifice and complexity in a life.

Marie Colvin is described at the beginning of Conroy’s book as marking her entry with explosive vitality and independence, as opposed to the lifeless media herd: “Suddenly [in a hotel room full of journalists in Syria in 2003] the door crashed open on this scene of total lassitude. A lone female appeared, wearing a battered brown suede jacket and with a black eyepatch covering her left eye… She paused as she observed the motley bunch of comatose journalists in front of her… ‘My God, [says Colvin,] they’re drugging the fucking journalists. They must be drugging the tea,’ she explained in absolute disgust.” Conroy recounts the exploits of Colvin and comments that the “legend” of Colvin that Conroy experienced and witnessed himself exemplifies “a reputation for being one of the last journalists to leave the world’s most dangerous places at their most dangerous times.” Colvin, says Conroy, was inside Gronzy in the Chechen Republic during a siege by Russian forces. “She barely made it out alive. She went days without food as the advancing Russian army forced her to flee for her life with the band of rebels she was with.” Conroy says, “She once stubbornly refused to abandon hundreds of refugees in East Timor as government soldiers marched on their camp,” when most of the other journalists decided it was too dangerous to stay. Colvin risks the vitality of her life and intensifies that vitality through risk. Her death is reported in the book in stark terms devoid of sentimentality and embellishment as a reflection of the bare truth the description. Some even believe that Colvin’s killing by the Syrian army was deliberate and an “assassination.”

Conroy’s book is rich in details that can be extracted about the state of mind and emotion of journalists as they engage in parrhesia in a crisis zone. The layers of significance are complex, familiar to journalists if not their audience. For instance, the book has a subtle journalists’ rating scheme that evaluates each of the journalists who come and go during the account, ridiculing some, finding others stalwart and stoical under the harshest of circumstances. As the risk escalates nearer to the brutal inevitability of death, notice is taken of who leaves, at what point they leave and how they justify their departure. So, one photojournalist whose credentials are that he “shoots mainly for The New York Times” was with Conroy “in Misrata [in Libya] when the siege was at its worst and most of the world’s press had abandoned the city.” And yet even this courageous photojournalist was worried by the plan of Colvin and Conroy to enter Baba Amr in Syria. Conroy says, “He told me that he wouldn’t even consider going in at this point.” Another courageous journalist says that “entering Syria was a cut-off point for her – she would not cross the border.” Colvin and Conroy return to the rebel media centre of the Free Syrian Army in the Baba Amr district of the city of Homs in Syria. The centre had already been damaged, although the rebels and Colvin continued to use it. The situation in Baba Amr had seemed to Colvin and Conroy to grow dangerously close to a final assault of government forces, so the two journalists had left, but then returned to the worsening siege of Baba Amr, believing, as the danger intensified, it was the essential ground zero for the story. The assault on Baba Amr was worse than in the Chechen Republic and Libya, Colvin says. (119, 130). “The ferocity of the attacks,” says Conroy,” made us even more determined to remain. Neither of us was inclined to take the easy way out by declaring the place too dangerous to work in.” The brutality strengthens the determination to report on what was happening. The degree of crisis is what makes the truth ultimate.

Conroy’s account of what he and Marie Colvin suffer and endure in the conflicts in Libya and Syria is based on an ideal version of what the journalist should be and what truths a journalist should expose. The two journalists went together into Baba Amr, being demolished as the most intense focus of the government forces of President Bashar al-Assad. (38). It was in Baba Amr that Colvin was killed in the media centre of the Free Syrian Army, where she had the crucial logistical support from the rebels that she needed to report in the country and was able to communicate her stories from their centre through the Internet without a greater risk of being detected. She and Colvin act so independently there that the words “outlaw” and “renegade” are applied to them too.

The point of the label of renegade for the journalists or for any citizen to stands in opposition to power is to assert radical independence and autonomy. But, considering this independence, did Colvin go too far in endangering herself and influencing others to take risks? Should editors exert more control over fiercely passionate journalists like Marie Colvin? Should a journalist be fired for disobeying an order over safety? Should an editor be fired for not protecting a journalist? The rebel media centre is described by Conroy as an outpost of “outlaw” media, and Colvin and Conroy, were, in a sense, outlaw media too, also hunted by Syrian government forces, breaking ranks with the other media, delinquent with editors and family. Colvin is described as a “black-robed renegade” and “brave renegade.” The two had “gone rogue” to return to the dangerous Baba Amr a second time, concealling it from their editors because they believed permission would be denied by the editors. There is a difference between journalists taking sole responsibility for their risks and for an editor to exert pressure on a journalist to take the same risks. It is the same with a teacher, parent or spouse, who would be justified to err on the side of caution when the life in their sphere of responsibility is at risk. At the same time, both Colvin and the editors are trying to calculate risks in unpredictable and changing situations without reliable information.

Everybody had a different perspective of the degree of the risk. Near the end, Conroy emails Colvin’s editor without Colvin’s knowledge from Baba Amr describing the risk in dire enough terms that would be expected to force the editor to order Colvin out, although Conroy doubts Colvin would obey an order. Conroy is obviously troubled by the growing danger but hesitant to be blunt with Colvin or to abandon her. Her passionate embodiment of the truth is too powerful a force. In response to Colvin’s email to the editor, the editor sends Colvin a conciliatory email praising her work, arguing against her strong sense of mission that there is not much more that could be accomplished with reporting, and saying, “I think you should consider leaving BA [Baba Amr] at the first opportunity.” The tone of the email suggests that Colvin has more power than the editor and needs to be persuaded and cajoled, not ordered. But at that crucial moment four more journalists arrive at the rebel media centre, emboldened to come there by seeing Colvin in a video in Baba Amr broadcast by Al Jazeera. The new arrivals, in turn, embolden everyone to stay longer. Marie Colvin and another journalist are killed the next morning by a rocket bombardment. Conroy and a female journalist are badly injured. That same year, 2012, the Committee to Protect Journalists said that 31 journalists were confirmed killed in Syria, the highest number for a country in the world that year at that time.

Conroy praises the courage and endurance of Colvin in a military-journalist way – “[Colvin] was calm under fire and reacted well to danger” – distinguishing her from other journalists and from the rebels who are helping them. At times during the book Conroy’s language dissolves the separation between soldier and journalist, identifying the rebels as “friends” and others as “the enemy.” With a rebel general, “She was tenacious and, where a lesser mortal might back down or be intimated, Marie would coax and persuade until she got what she wanted.” Marie Colvin also endures as a journalist a life reduced to the bare essentials of poverty, hunger, anxiety, suffering and reliance on others, like a mendicant monk pursuing a spiritual mission.

In contrast, a French journalist joining their secret trip across the border to Syria with Sunni rebels was “unknown to both of us” and needed to be tested. Conroy tells the French journalist that a source of his in the Lebanese intelligence service told him “that there were orders for any western journalists caught around Homs [in Syria] to be executed on the spot and their bodies thrown into the battlefield.” The French journalist passes the test by being undeterred and unwavering at this news, his only comment asking if he can quote in a story what Conroy said about journalists being executed if caught. Later, Conroy thinks the journalist is not fit enough physically or temperamentally for what must be endured. He is mocked for wearing longjohns for pyjamas in a war zone and Conroy notes that fear breaks out in the French journalist in an “anxiety attack” going through a three-kilometre tunnel into Baba Amr.

In a similar way, the courage of Colvin and Conroy is depicted as mature and balanced, neither denying fear nor being overwhelmed by it, and is contrasted at times with the rebels, who are courageous but also sometimes described as reckless, foolhardy, nonchalant and dependent on their god for protection. Thus, running the gauntlet in Syria exposed to sniper bullets and rocket-propelled grenades with the journalists as their cargo, the rebels need to stay hidden but expose themselves by singing loudly or playing the radio loudly or shouting appeals to Allah.

Conroy believes it necessary to be clear that the purposes of Colvin in reporting were pure and not motivated by superficial or egotistical personal motives. When Conroy does this, he is appealing to an implied ideal norm that Colvin is acting for a higher purpose in seeking the truth. She embodies her compassion for the victims of war and conflict by seeking a pure truth, not acting out of narrow self-interest. Conroy is discriminating in a way that indicates he has implicitly formulated the conditions for a altruistic parrhesia that someone would need to meet. Thus, Colvin was not motivated merely to scoop other journalists, says Conroy, although that is always satisfying. The implication is that merely being concerned with beating the competition in a story would be superficial and just serve a career personally. It would not be true courage, but a calculated transaction for personal glory or the promotion of a career. In the same way, the courage of Socrates would be tainted by impure motives. We wouldn’t admire a Socrates who was merely thoughtlessly reckless in what he says or just seeking public attention, as happens today on social media where truth and a Socratic parrhesia are corrupted by the desire to win attention by being outrageous. That’s not the virtue of courage in speaking the truth. Nor was Colvin she merely a thrill seeker, says Conroy. “Instead, she was driven by a deep sense of moral outrage at the suffering of civilians who are inextricably caught up in the bloody conflicts around the world.” Colvin “argued passionately for the need to send reporters to dangerous places.” For her, says Conroy, reporting on wars was “a way of speaking truth to power,” of “bearing witness to the plight of ordinary citizens,” of holding governments accountable by speaking to the public. “Marie was at her best when she had a cause for which she could use her insightful and tenacious journalistic skills. In Baba Amr, as in other conflicts, she found her purpose in describing the humanitarian costs that war forced civilians to pay. She would give them a voice and put them on center stage.” The final deciding factor is that civilians are being slaughtered in Syria and “bearing witness to the bloody impact of war was what Marie was all about.” Her moral outrage “drove her to cover conflicts when she was well into her fifties,” like “her journalistic heroine,” Martha Gellhorn, a war correspondent of the previous generation for almost 50 years.

Before Marie Colvin, Gellhorn was covering wars and conflict around the world, including the Spanish Civil War, the Second World War, the Vietnam War, Arab-Israeli conflicts, and wars in Central America. During the Second World War, when female journalists were forbidden from covering the front with male journalists, Gellhorn hid herself as a stollaway in a hospital ship to witness the D-Day landing in Normandy. A history of parrhesia in journalism could be written of journalists similar to Gellhorn and Colvin who pursued the riskiest truths personally, from Nelly Bly in the late 1800s and including among others, like Ernest Hemingway and the assassinated Irish journalist Veronica Guernin. Women journalists were also breaking gender barriers at the same time.

Colvin believed the significant story was typically the suffering of the innocent victims, which could not be reported in its fullest and most powerful way from either government or rebel sources. It was not an abstract truth of numbers or of ideology. Conroy says, “both of us were aware that reaching Baba Amr would bring our piece to life.” In an email from Colvin to Sean Ryan, the foreign editor of The Sunday Times, five days before she was killed, which is quoted by Jon Swain, Colvin explained during her final time in Baba Amr, “I feel strongly that we have to include these stories of the suffering of civilians to get the point across.” Colvin was broadcast on CNN from Syria saying that she had watched a baby die and, “It is a complete and utter lie they’re only going after terrorists. The Syrian army is simply shelling a city of cold, starving civilians.” Conroy sent an email to the editor that the high public profile of Colvin in exposing what was happening in Syria was so dangerous that it made them all targets.

So, can there be truth in human affairs without a particular witness, a risk, a contrary force? Is a distinct form of truth forged by a witness who takes a dangerous risk to speak for a justified purpose that is essential to that truth?

If this kind of risk, of parrhesia, of journalism and of citizens protesting publicly against power do truly produce an essential form of truth, what happens in an era of the Internet and social media?

As the role of professional journalism dwindles, will citizens use the internet to tell the dangerous truths? Or will these truths be overwhelmed by deception, evasion and distraction?

Time will have to provide the answers. In Foucault’s analysis, the concept of parrhesia was being forged in ancient Greece and Rome. In Athens, at the time of Socrates and Plato, democracy was a delicate experiment prone to manipulation and abuse by sophists. The truth of that is being played out now in the United States and other countries with sophists like Donald Trump. As Plato knew and as Foucault explores, there was doubt how well parrhesia worked in a democracy like Athens. Socrates was speaking out because he believed that the voice of truth was being lost by the power of the sophists to persuade gullible citizens who couldn’t think clearly for themselves, who couldn’t even define courage or know how to find the truth. Plato predicted the risk in a democracy from a politically successful rhetorician and sophist like a Donald Trump. Trump is powerful because sophistry has a powerful effect on people. Plato's antidote was the the figure of a Socrates and the human capacity for parrhesia.

If there is a potential and faculty for inquiry that is embodied in Socrates, in particular ways that don’t exhaust the potential, are journalists, protesters and truth-seekers other particular embodiments of a Socratic spirit? If so, who are these other people?

Is there a Socratic spirit strong enough in our time to guide people away from sophistry? Will Socratic parrhesia survive? Or, will Socrates be drinking hemlock perpetually in punishment for a truthfulness that others can’t tolerate?

email: socraticzen88@gmail.com

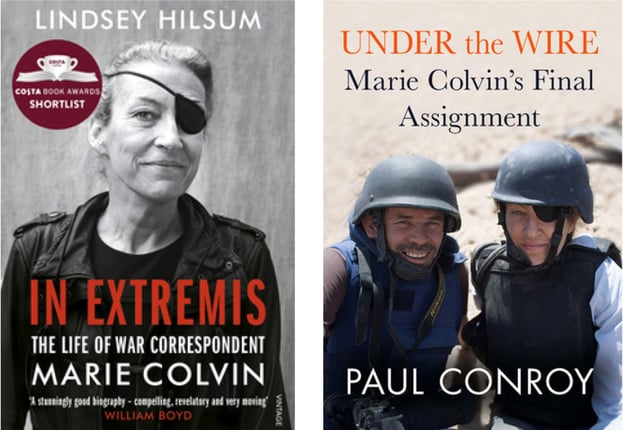

The unusual courage of journalist Marie Colvin is chronicled in two books, a biography by fellow journalist Lindsey Hilsum and a personal account by photojournalist Paul Conroy, who was with Colvin when she was killed in Syria and Conroy badly injured.

Socrates as a warrior showed courage in battle in word and deed. Image from an idea by Shawn Thompson

Can you begin with a question and end with a question?

Making contact:

© 2024. All rights reserved. Copyright Shawn Thompson

Socratic Zen on Meta (Facebook) as an interactive public forum

Socratic Zen on Youtube (under construction)

The font used for titles for this website is Luminari, an exquisite yet restrained script font designed by a company called CanadaType. "Its majuscules are particularly influenced by the versals found in the famous Monmouth psalters, as well as those done by the Ramsey Abbey abbots in the twelfth century."

Find an explanation at https://canadatype.com/product/luminari/