Chapter 4: How does the dead tree sing in the wind?

Wherein we learn of the oak tree, big radishes, a seven-pound hempen shirt and killing the Buddha

Shawn Thompson

5/28/202410 min read

In the Buddhist Zen literature, the koan “Joshu’s dog” from the 1229 AD Zen collection Mumonkan or The Gateless Gate is well known and much discussed. Joshu Jushin lived in China, apparently from 778 AD to 897, and, according to the story, died when he was about 120 years old, which is miraculous. That may not be literally true. But maybe it is. Joshu is credited with 21 koans in Mumonkan and the Hekiganroku, which is not a bad heritage. The story of “Joshu’s dog” is a koan or bewildering statement where the experience of the koan is the point. It is a kind of magical thinking or miracle wisdom, which delights and entertains and instructs by defying our expectations and our understanding. Like magic and miracles, the koan should make us curious because magic and miracles are beyond rational explanation. A number of the koan stories are magical events, which may make rational westerners skeptical. In any event, before Joshua became a Zen master, he practiced Zen under another famous master, Nansen, who, according to the story, killed a cat as a lesson to the monks. In the story of Joshu’s dog, a monk asks the master, Joshu, who doesn’t actually have a dog, if a dog has a Buddha nature. The question is very simple, a practical test for the wisdom of the master. It may be a clever student trying to trick the master, as clever students sometimes want to do. It is part of an agon, a contest, a Dharma battle, in ancient Zen Buddhism. But, in cases like this, the question comes from a rational ego full of pride and arrogance, seeking merely to defeat another person in the combat of debate. The greater the stature of the master, the greater the victory for the ego. That’s how the ego thinks. But it is a closed gate. The inclination is to the analyze the question to produce a clear, definitive answer. What is a Buddha nature? What is a dog? In what sense is a dog comparable to a human being? What are the criteria for the comparison of a dog to a human being? Those questions in themselves can lead to debate, but the debate doesn’t get closer to an answer - which may not be a bad thing. But the story of the dog is usually not explained with that kind of rational analysis. Instead, the master answers with apparent finality, “mu,” a word usually translated from the Chinese as “no,” “nothing” or “non-being.” So, what kind of an answer is this? And why should the student be enlightened by this answer? Hasn’t the master literally answered the question by saying a dog does not have Buddha nature, in which case, why is this episode so cherished and how did it find its way into The Gateless Gate? Or does “no” mean the question is bad or an answer to it irrelevant?

This Mu experience is therapy for the soul or psyche in Zen Buddhism, as also in the elenchus of Socrates also with an individual and in an individual therapy session with a therapist. The spirituality and the transformation are in the experience, not in the dogma. It is a common reflection that the word “psyche,” as used in psychology, comes from Greek word spsukhe, for breath, life and soul. That doesn’t mean that the common word hasn’t changed and means the same in all uses. But there is some similarity in the uses of psyche and soul and some distinctions. Mainly it seems to mean experience outside the realm of rationality, outside the conscious self, and outside what psychology calls the ego consciousness. What that outside is, is another matter. But is this practical for the world we live in, where at some point we have to make a decision and take action? Can the therapy of the question have a practical value in society? Can a Zen Buddhist be a political leader in our world? Might it work? Or is what is attainable as an individual level simply unattainable at a large group level in society?

One classic interpretation of the Mu episode comes from Mumon, the monk named Ekai. The question is a literal, binary, yes/no, either/or question. Binary questions are useful to achieve clarity but can otherwise be misleading with a false binary choice. For a binary question like this, either a dog has Buddha nature or it doesn’t. If a dog were involved, as with Nansen’s cat, which is another koan in The Gateless Gate, then Joshu would say, if you get the wrong answer, the dog will be killed. The question is a clever trap in a yes-or-no context. If a dog were involved, the dog would be killed – as was Nansen’s cat - if the answer was either yes or no. Both answers are wrong. But Zen masters were probably not killing animals for emphasis. There is no dog in this story to add that emphasis. No slap to the face as the answer. The answer to the question put to Joshua is an obstacle and intended as an obstacle, for those who understand how the answer is an obstacle. Before this, Joshu got a lesson in this from Nansen, who seemed to be giving him paradoxical guidance in finding the Way of Buddhism. Nansen told Joshu, “The Way is not a matter of knowing or not knowing. Knowing is delusion; not knowing is confusion.” That kind of response was apparently typical of Nansen. Both answers are wrong. It’s not binary. Mumon comments on Nansen, “Let the mountains become the sea; I’ll give you no comment.” Mumon says that it took “another thirty years” for Joshu to understand the original lesson from Nansen this fully, but then Joshu lived to be about 120.

“Enlightenment,” comments Mumon, “always comes after the road of thinking is blocked.” So, says Mumon, “Summon up a spirit of great doubt and concentrate on this word ‘Mu.’ Carry it continuously day and night. Do not form a nihilistic conception of vacancy, or a relative conception of ‘has’ or “has not.’” In a state of doubt, a person must literally live with the activity that the question creates, rather than answering the question and putting an abrupt end to the exercise. As Joshu says in the koan “The real way is not difficult,” when a monk pesters him for answers, “Asking the question is good enough.” Joshu says, borrowing the words of someone else, that the Way “only abhors choice and attachment,” factors which would be found in an answer or a bad question, among other things. As Katsuki Sekida explains, “Joshu has no attachment, not even to enlightenment.” Whew. That’s a provocative thought. Even enlightenment can become a form of dogma. The enlightened are unenlightened. Whosoever will enter the kingdom, must become a child again. No dogma allowed through. The answer “mu,” says Mumon – whose name, in translation at least, seems to include “mu” – is: “do not believe it it the common negative symbol meaning nothing. It is not nothingness, the opposite of existence.” Subjectivity and objectivity “become one.” Mumon said, commenting on Joshua’s Mu, that, “when you meet a Buddha, you will kill him,” which Sheldon Kopp takes as the title for his fascinating book, If You Meet the Buddha on the Road, Kill Him: The Pilgrimage of Psychotherapy Patients. The violent comment to kill the Buddha is one line without elaboration. It seems obvious that this statement is not meant to be taken literally. Unfortunately, people who are too literal minded, of which there are too many in the world, would be killing Buddhas and others. That’s the risk of using metaphors with people without the capacity to understand them. That’s also the risk that spiritual literature takes when it needs metaphors to explain what is beyond literal thinking. Sometimes though, an earlier text is interpreted more compassionately, to mean that what was once intended as literal, is now best understood as metaphoric. In either case, that’s some kind of progress. So, when Mumon says he was “homeless,” he doesn’t mean literally homeless, but divested of the errors in point of view that had become familiar to him.[xviii] Literalness doesn’t apply. The search for meaning comes from discarding what seems literal. Mumon explains that the process of staying with the question of Mu, “It is like a dumb man who has had a dream. He knows about it but he cannot tell it.” The enlightenment is like a dream state that is experienced with clarity but cannot be articulated rationally. If a person succumbs to an either/or mindset, the Buddha nature is lost. Mumon in essence is saying. “Mu has no meaning whatsoever.” There is no answer to the question, only an experience of being inside the question as though being literally in a dream.

The typical Zen question might be added, Who in us creates the dreams that we experience? That bewildering question can only be experienced by an individual, not explained rationally in words. An authoritative, rational explanation would become dogma, which is not the purpose of the koan. Dogmas turn individuals into conformity to an abstract norm where they lose their individuality. However, believing in dogma is a strong temptation for human beings. It can be very satisfying. But a non-literal interpretation can also become another dogma, however ingenious it is. Basically, paradoxically, if you don’t experience the unanswered state of the question, you don’t have an answer. Thinking in terms of question and answer is thinking in binary terms. But even that explanation is from a waking state, from a rational, conscious state, not experiencing the dream as an individual. Your own genuine experience is your own genuine answer, as long as it is genuine. Figuring out what is genuine is another bewildering task, which would make it a good question. How would you know that you aren’t self-deceived when you think you are being genuine? How would you know that you are self-deceived?

From a rational, western point of view the goal in Mu and Zen experience is a radical departure. It is at odds with the western premise of the primacy of the answer over the question. Instead, in Zen, the question has primacy over the answer. The goal is the experience of the question. The same concept may be found in the Socratic aporia, or bewildering inconclusiveness of the elenchus, the agon of questioning for the benefit of those involved. The aporia is found in the early dialogues, but disappears in the later ones, as Plato becomes more assertive and dogmatic. The western literature on Socrates, taking a rational point of view, has trouble finding meaning in this aporia that resembles a Zen experience. Is the result stalemate, stasis, no prospect of an answer that can guide action? Even the apparently weak resolution of this problem of the aporia, from a comment of Socrates that he is helping others find the truth by first cleansing their minds of their delusions, has the premise that what would come afterwards, but hasn’t been attained yet, is the truth. That makes perfect sense from the rational western point of view, but not from a Zen Buddhist point of view. But has this now become another deceptive Mu either-or question, either a rational or a Zen point of view is correct? Some would say yes. Others might say that the question is the problem.

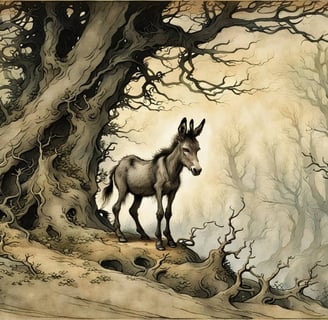

Another famous Zen koan in The Gateless Gate comes from Joshu and is reminiscent of “Joshu’s dog.” This one is Joshu’s oak tree. Is this also Mu? A monk asks Joshu – whose name may come from the area where he lived - what the coming of patriarch from the west means. It is another agon or test of the master. Joshua says, “The oak tree in the garden.” Apparently, there were a lot of oak trees where Joshu lived, but that that solution seems too literal. But maybe there was an intention in picking something that is common, rather than exotic. Just another oak tree? Is the answer that easy? An oak tree seems somewhat specific, why not a cypress tree or an olive tree or any other tree? And why out of the west, which seems like a significant distinction? Every oak tree is different and yet still an oak tree. One interpretation in the literature is that a tree is oneness and everything. Is this about treeness and difference? The oak tree is too specific to seem literal, so it seems to be a metaphor. Since trees are archetypal symbols and appear in all kinds of myth and folklore, the temptation is to fit the tree to a common archetypal symbol. The typical bewildering koan does not give enough information to guide an interpretation and that is deliberate. Since a tree is easy to understand as a symbol, there are convincing interpretations of this koan. Are they all correct or is one more correct than the others? A further complication with Joshu’s oak tree is another story that a discipline of Joshua was asked about Joshu’s answer of the oak tree. The disciple denied the koan. But is the denial true? And what would it matter if this koan were a fiction if it was a genuine koan? Wouldn’t it be genuine not because it is a historical fact, but because it was in the true spirit of Zen? If Socrates were discussing interpretations of this koan with a Zen devotee, he would bring it to aporia. Yes, indeed, whatever the case, there is a zenfulness to the denial, to the aporia, for which we should be grateful. But, then, maybe an oak tree is just an oak tree and nothing more – and maybe even that is not the lesson, because the lesson is Mu. Engo comments on Joshu’s koan with another koan, “thorns in the mud,” which is the same comment of Mumon when Joshu investigates what an old woman in a tea booth said without saying what he found. It makes sense to avoid the trap of making definitive interpretations by responding to one koan with another koan. As Joshu would say, it’s a big raddish.

And so it goes with Nansen, Joshu, Mumon. The answers that Joshu gives at various times are Mu, the oak tree, big radishes, a seven-pound hempen shirt, north-south-east-west, a wooden Buddha burns in fire, the question is good enough. He has learned well in about 120 years and tried to avoid preaching dogma. There seems to be a similarity in these koans of Joshu, which could mean that this is consistent with Joshu or it could mean that koans that would sound like what Joshu would say, are then catalogued as the sayings of Joshua. Who would tell the difference, if the differences even matters? What is Buddha? Three pounds of flax, says Tozan Shusho. Dung, says Ummon, being more expressive. Anything can become formulaic, even koans like this. So, don’t succumb to the formula, as difficult as that sounds. Enter the experience of doubt as though it is not doubt but peace of mind, not the formula of doubt. Be, as Setcho says, the dead tree singing in the wind. Be the tune of the oak tree, the memory of the cypress tree, the curiosity of the olive tree, the wind that sways none of them.

email: socraticzen88@gmail.com

Image from an original idea by Shawn Thompson

Can you begin with a question and end with a question?

Making contact:

© 2024. All rights reserved. Copyright Shawn Thompson

Socratic Zen on Meta (Facebook) as an interactive public forum

Socratic Zen on Youtube (under construction)

The font used for titles for this website is Luminari, an exquisite yet restrained script font designed by a company called CanadaType. "Its majuscules are particularly influenced by the versals found in the famous Monmouth psalters, as well as those done by the Ramsey Abbey abbots in the twelfth century."

Find an explanation at https://canadatype.com/product/luminari/